Breathing New Life into Heritage Buildings

And Why it Matters

There are 4,891 entries in the Historic England Heritage at Risk Register published in November 2025. Of these heritage buildings, places of worship are the third largest group, with 58 new places of worship added last year. And these figures should be read with the understanding that the Register only identifies sites most at risk of being lost as a result of neglect, decay or inappropriate development. It’s safe to assume that there are plenty more heritage buildings in England that are at risk and for a variety of reasons.

Emotional anchors

When it comes to saving our old and heritage buildings, it would be wrong to just focus on places of worship, but these do often hold a particular place, as well as presenting a number of unique challenges in many communities. They are often emotional anchors. They hold cherished memories, happy and sad. They are a place of spirituality, of escape and reflection, but also often a social and community space, a central hub for a village. More often than not, they come with a long (and sometimes) important history. So even though congregation sizes may have shrunk, they remain an important place.

Improving lives

Historic England explains that “Looking after and investing in these historic buildings and sites is key to creating successful places that help to improve people’s lives”. After all, heritage buildings within a community are a source of pride and inspiration, and have the potential to enhance the local economy, whether as a tourist attraction, an office space or by creating job opportunities for skilled craftsmen or with local work opportunities. And of course, and perhaps most importantly, there is a sustainability issue at work here too, and an opportunity to help to address climate change. With all this in mind, most communities want to save their historic buildings and that means that the question really changes from whether these buildings should be saved to how.

Resistance to change

However, it should also come as no surprise that many communities are resistant to change. And this reluctance is often then fuelled by a misunderstanding or in some cases, a lack of information about what any restoration, redevelopment or repurposing of a building might result in. Fear (of over-development, unsympathetic restoration, modern buildings in a rural area, business and traffic intrusion) is a powerful driver. Not to mention the challenges that can come with planning permissions and listed status.

But with shrinking congregations and budgets, combined with material deterioration of heritage buildings, rising heating bills and inaccessible layouts, it’s more important than ever to shift the focus from “loss” to “stewardship.” If we don’t, many buildings will simply run out of time.

So, what’s the answer?

The overarching answer is intelligent, respectful architectural design. This can take many forms, but done well, can save and even enhance the integrity of a building whilst giving it a whole new lease of life.

Shared use

Many historic churches are finding new life through thoughtful shared use, balancing worship with a wide range of community activities in a way that strengthens their long-term sustainability. Sundays remain devoted to religious services, while during the week these buildings host anything from adult learning, music rehearsals to co-working. This dual purpose not only reconnects churches with the communities they were built to serve, but also generates essential income, helping to secure their future without losing their spiritual heart.

Sensitive adaptations

Of course, transformation of a heritage building depends on sensitive architectural design that respects heritage while enabling flexibility. Fixed pews could be replaced with movable seating, allowing spaces to adapt without permanent alteration. Discreet partitions create smaller, usable areas without disrupting historic sightlines, while carefully improved acoustics ensure the building works equally well for worship, music and conversation. When done well, these interventions protect the character of historic churches, proving that preservation and modern use can coexist and that living buildings are often the best way to save them.

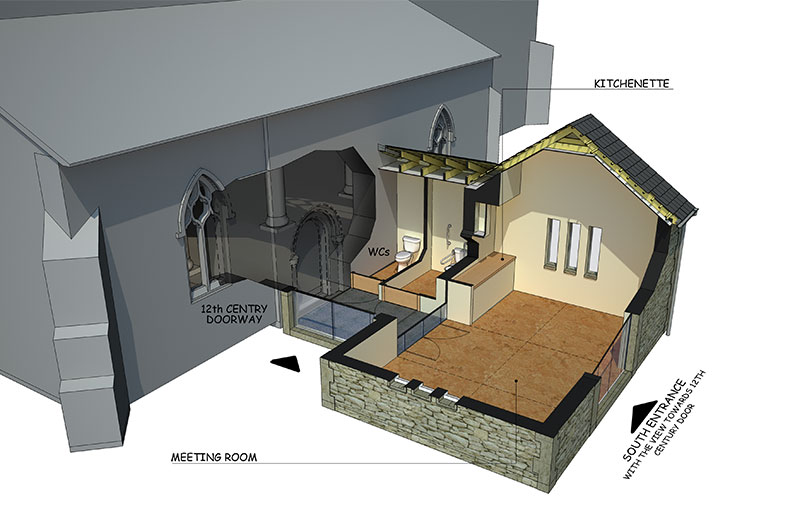

Extensions and additions: creating new space

Carefully designed extensions and additions can also play a vital role, allowing new functions to be accommodated without compromising the integrity of the original structure. By locating essential facilities such as toilets, kitchens, meeting rooms, storage and accessible entrances within discreet annexes, the historic core is protected from intrusive alteration. When approached as “quiet architecture”, these modern additions are intentionally restrained in form and material, clearly contemporary yet deferential to the original fabric.

Upgrading facilities

Alongside new space, sensitive upgrades to existing facilities are essential for keeping heritage buildings viable in modern use. Technological advances mean that heating systems such as underfloor heating, air-source heat pumps and zoned controls allow spaces to be warmed efficiently and only when needed, reducing both energy use and visual impact. Carefully planned lighting schemes using low-glare LEDs can highlight stonework and architectural detail rather than overpower it, while accessibility improvements (ramps, lifts, hearing loops and level thresholds) ensure inclusivity without eroding character. Measures such as secondary glazing, draught-proofing and discreet insulation further improve energy efficiency.

Repurposing

There will, of course, be occasions where maintaining a building for its current purpose (be that a place of worship or something else), is simply no longer possible. But far from being the enemy, sympathetic repurposing of the building to create a home or office space may be the only way to not only save a building but to save it in a way that respects it architecturally.

Sensitive interventions are often both restrained and reversible: freestanding insertions, subtle zoning and a clear hierarchy between old and new. For example, kitchens, bathrooms and bedrooms could be housed in freestanding pods or tucked into existing ancillary spaces, so that the primary form of the church remains intact. New floors or mezzanines can be introduced but historic walls, windows and roof structures can be left visible. Materials can be chosen to complement what is there, and modern services such as insulation and heating can be discreetly integrated.

Communication, planning and funding

Of course, behind every successful adaptation sits a careful framework of planning, permissions, funding and communication. Early, informed conversations with conservation officers and church authorities can make the difference between a smooth project and a stalled one, particularly where faculty jurisdiction and listed building consent overlap.

Equally important is funding and community support. Churches that remain active and shared are often better placed to access grants and new funding streams, but lasting success depends on consultation and local buy-in from the outset. And we’ll look at all these issues in greater detail in our next article.

Ultimately, however, sensitive adaptation is not about erasing the past; it is about ensuring these historic buildings continue to live, serve and evolve. And on the plus side, 37 places of worship were removed from the Historic England Heritage at Risk Register last year.

If you would like to discuss options in respect of a heritage building, please get in touch.